Dixie's Land

Author: Daniel Emmett

Date/Studio: 1981 Spectrum, Portland, OR

Engineer: Dave Mathew

Producer: Baila Dworsky

Original Release: The Art of Dulcimer (KM217)

Current Release: The Complete Recordings (BSR 158)

Albert was a history major and loved exploring the oftentimes obscurity of the origin of things. Dixie's Land (Dixie) has a storied past. Having been born in New Orleans, Albert was keen on adapting a version for us to have in the repertoire since we were playing at many folk festivals across the South.

Albert was a history major and loved exploring the oftentimes obscurity of the origin of things. Dixie's Land (Dixie) has a storied past. Having been born in New Orleans, Albert was keen on adapting a version for us to have in the repertoire since we were playing at many folk festivals across the South.

It's the Broadway stage in 1859. Daniel Decatur Emmett has to come up with a ditty for what was called “travelin' music.” Bryant's Minstrel Show needed a catchy tune to pull people in off of the streets. Emmett's job was to draw folks in by strolling around in front of the theater singing and playing. It was cold and grey in New York City. What better way to escape the grey of the city streets than through a song? He came up with a jumpy tune to play outside for Bryant's black-face minstrel troupe. Its catchy refrain, “I wish I was in Dixie”, became a big hit.

As the song’s fame spread, it began to win affection in the South, especially as state after state swept into Secession. Confederate Brigadier General Albert Pike wrote new words and by popular acclaim, “Dixie's Land” and his new words became the national anthem of the Confederacy. After the war, Pike's words were largely forgotten. Emmett's original verses are what everyone sings today.

Albert certainly infected me with the desire to know what is the history that lies behind the images of songs and stories. I love the idea that especially folk music chronicles and preserves the times, events and passions that would otherwise be swept from collective memory. For instance, in Dixie's Land, Emmett has Will the weaver smiling as fierce as a forty-pounder, a cannon almost five inches across. That's a grim fierceness indeed that bespoke the times.

The word, Dixie, had to come from somewhere. Most historians maintain that “Dixie,” came from the New Orleans Creole banking houses’ ten-dollar bill, the dix. My Dad, a logger out in the West, called the ten-dollar bill a sawbuck. Most entomological sources credit this term as coming from the X-shape of a woodcutter’s jig and the Roman numeral for ten. See. Once you get going on this kind of research it’s addictive. I believe folk songs are one of our best sources for hearing voices of the common people-- not the ones who make (and rewrite) history but rather, the ones who live it day to day.

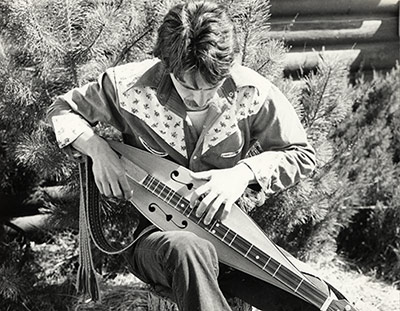

In our rendition we wanted the opening three notes of the tune to really stand out. Rather than playing it as a cakewalk or shuffle, we wanted a more martial, march-like feeling to the tune-- a tempo that reflected bravery and optimism and the quick-step of those striding forth with purpose and commitment. We accomplish this by striking the dulcimer forcefully across the strings in a full-strum downbeat while rapidly pulling off the sol-me (5-3) notes. That starts the tune percussively. Next there is a staccato effect that can be accomplished by chopping at the strings in a cut-time rhythm.

When we get to the lyric line, look away, we syncopate the rhythm. It helps the tune to stay lively. Another technique that characterizes our rendition is that the bass string is often fretted as a parallel voice to the treble melody. This adds great tone contrast. One more device we employ is to flat-pick (arpeggiate) the chords at the top of the each refrain. This gets the notes ringing out individually in contrast to the two-stop-chord fullness of the rest of the song.

Finally, almost operatically, we close the song with a long retard-- a slowing down of the melody that eventually builds to a crescendo. We set it up with a reprise on the phrases, away, away --repeating that part of the melody five times and breaking out of it with full-length octave slide on the word, south, (down south in Dixie). We trail off at the end with more flat-picked arpeggios.