Tiger Dreams Blaine Street Records BSR101

This CDR is now incorporated into a two-compact-disc set: BSR 158

This CDR is now incorporated into a two-compact-disc set: BSR 158

The Complete Works of Robert Force and Albert d'Ossche'

Available through CD Baby and i-Tunes. Five albums in one.

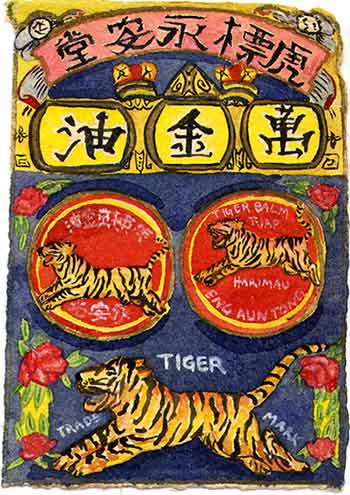

These are F/d'O up-tempo tunes excerpted from three Kicking Mule albums. The original watercolor art is by Martha Worthley. I thought it appropriate-- songs from the Dreamtime of we as young tigers. (Many of Martha’s beautiful fine art works can be viewed by Googling: martha worthley port townsend.)

In 2000, after a ten-year hiatus, I went back to accepting limited bookings-- usually 8 to 12 a year. As soon as I got “out there” it was clear that although many of the old guard knew me and my work, the folks coming up had no real idea of the music I played. Some of my tunes were known, played and being passed along but my twenty years of performance, recording and publishing was barely a blip in the new marketplace. It was time to get the tunes back out. “Hand-made” CDRs offered that option.

Sitting in my basement is an old, insulated, cedar pie safe. That's where I had stored all of my 2-inch, reel-to-reel studio masters. These were the raw, multi-track originals. Alongside of them were usually two, still-in-the-shrink-wrap copies of my albums I had set aside unopened. Beside them were test pressings of the albums. Finally, there were ¼-inch tape, half-track, mixed masters of the productions.

There were very few machines around that actually still worked and could play 16 and 24-track 2-inch tape. Even if there were, I would have had to remix every tune from scratch. Impossible. The virgin vinyl transfer process was not yet a reliable option. Today there are turntables and software capable of “ripping” vinyl records to digital. Back then there wasn't. My last option was both scary and final.

My all-around tech guru go-to and friend, Joe Breskin, researched the topic and came up with this answer: the ¼ masters could be baked in a convection oven at 130 degrees Fahrenheit for 4-6 hours and then played ONE time before the flux on the tapes flaked off. This process dried out the “sticky-binder” but also made the tapes brittle and the flux bonding unstable.

Port Townsend's Synergy Studio owner and engineer, Neville Pearsall, agreed to do the deed. Even if it succeeded, we might still have had “print-through” where the layers of the magnetically-charged tape leaks it's “stored” signal onto the other wraps. This would create pre- or post-echos depending on whether the tape had been wound “tails out” (the studio way) or had been run back to heads out.

We went ahead doing the best we could with the best information we had. Like polishing a Ming vase, we were doing our best to get it done and not drop it. We had those few vinyl records, so the music would not be totally lost if it didn't work. Still... (mmm) … (umm) ... It worked! Now for part B. When the tapes were run over the heads of the transport (recorder) the machine still had to be stopped after every song and have its ceramic heads wiped down with a q-tip soaked in anhydrous alcohol.

Cut by cut, 31 tunes and one bonus, unreleased out-take were lifted off of the six reels of tape thanks to Joe and Neville. Whew. It was now digitized. The project next went to Chris Martin at Peacebarn Studios. Chris' job was to fix any tape hiss and bass-wolfing “wow” flutters that might have crept in. All this was done in painstaking “real time”. No digital shortcuts. What you hear is what you get.

Finally Chris had to equalize the songs . The way I wanted to re-release the cuts they would no longer be either in the sequence or from the album on which they originally appeared. Fast songs went on Tiger Dreams. Slow songs went to Transformation. Instrumentals went into Wellyn.